"How you do anything is how you do everything” – Tom Waits

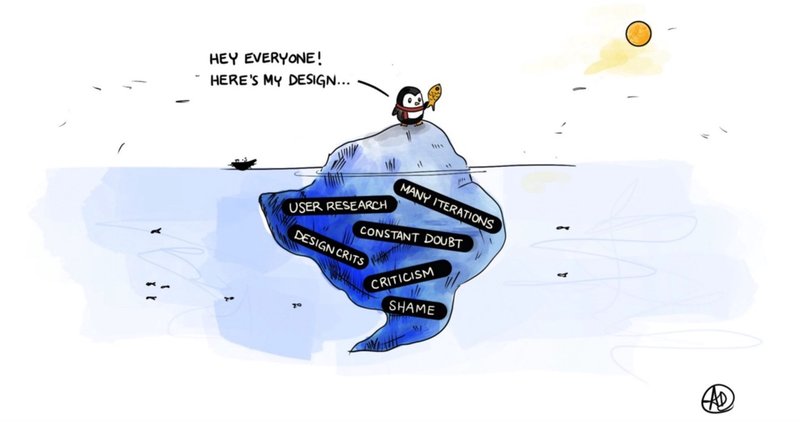

Image by Aletheia Delivre

“Show up as your authentic self!” If you’ve ever been the target of an algorithm advert interrupting a YouTube TedTalk binge session listing all the ways in which you should “be brave” “let go of your fear” “because this is how true connections form” in between some selfie-angled shot of a very good-looking person positioned in front of a window (so that light hits in just the right way) saying words along the lines of “have the courage to be vulnerable” “I made millions but I had no friends” “now, I have millions and I have friends” “I’m willing to share my secrets with you” “because it’s just too good not to share” “all for the nominal fee of…” Then, perhaps you feel similarly disillusioned by the oftentimes overused words: “authenticity” and “vulnerability” as the key to “great success” in marketing media and self-help cult guides.

Similarly, the word ‘Agile’ alongside others like ‘innovation’ ‘synergy’ ‘growth hacking’ ‘disruption’ and ‘alignment’ are words that have been exhausted by casual overuse. Consequently, many of us tend to disregard the impact they may have when used respectfully and sincerely within the correct context. ‘Agile,’ as with all of these other words, offers a practical, central tenet - which is the ability for teams to adapt quickly by facilitating cross-collaboration on the basis of trust and effective communication. And, disillusionment aside, all are critical to the design and build of products and services that effectively solve complex problems and meet user needs.

So why then this great feeling of disillusionment when words like “vulnerability” and “authenticity,” are used? Ironically - the very mechanisms that I feel repulsion toward have also been the very same that have actually enabled the widespread conversation around “vulnerability” and “authenticity” integral to the slowly rising formation of healthier working conditions that - at least on the outset - we seem to be progressing towards (in comparison to working conditions of e.g. the 1960’s). And, to my knowledge, were, in fact, first brought into the sphere of mainstream public debate by a number of global business thought leaders such as Mike Robbins who coined the phrase “bring your whole self to work” in his 2015 viral TedTalk.

And 5 years prior to this (2010), Brene Brown, whose social science research spanned over two decades before spilling out into a series of equally viral TedTalks, conference headlines, high-calibre talk show interviews and best-selling books (amongst many others). Whatever our feelings on the monetary capitalization of human fragility, objectively, what can undoubtedly be commended is Robbins and Brown’s achievement in having sparked a litany of constructive debate around the reality and nuances of “vulnerability” as it applies within the work environment across a broad spectrum of communities. A debate that even up until now, in 2022, is still ongoing.

To Be… Or not to Be… [Vulnerable].

What is the actual question?

To debate the viability of “bringing your whole self to work” as the mechanism to healthier and productive work environments is to first debate the nature of “vulnerability.” It’s within this debate that you first begin to see the fissures forming that ultimately separate camp: ‘pro-let’s-bring-our-whole-selves-to-work’ from camp: ‘definitely-lets-not-do-that-that’s-a-hard-no.’ It’s also where most of my cynicism tends to stem from.

In truth, ‘vulnerability’ means different things to different people. Since we cannot escape that the world has been unequal, each of us contend with varying degrees of privilege which, depending on circumstance and context, yield completely varying self- and co-perceptions. Any kind of debate that centres around trying to validate or invalidate our assumptions around each other’s perceptions can quickly evolve from a tiny little matchstick light into a harrowing wildfire.

By this I mean that: 2 or 3 or 4 or 20 people can be in the same room, having the exact same conversation or experience and depending on the nature of the lens of their past experiences, can come to perceive the outcome of that conversation or experience completely differently. The more people in the room, the greater the ensuing social complexity - the greater the variance in perception, the greater the disrepute in acknowledgement of each other’s vulnerabilities. Accidentally tread on an insecurity and whoops you’ve just detonated a landmine. This happens to all of us - as Timothy Morton writes: “to be human is to be wounded.” And as the Oxford dictionary implies: “to be vulnerable, is to have a wound that can be pierced.” If I’m cynical at all, it’s only that I, like most, have been wounded. My cynicism wraps around these vulnerabilities like inflammation to an injury.

The Problem with Invulnerability

Zoning in on this character trait - a tendency towards cynicism - which implies a belief that people cannot be trusted and pit it up against the social framing that healthy relationships are formed on the basis of trust and pit this up against the objective reality that the achievement of absolutely anything - work or social - relies on a network of healthy relationships. Often, the very defences our minds build up in the process of trying to safeguard us against the repetition of painful past experiences or imagined future worst case scenarios actually hold us back because they rob us of the opportunity to be proven wrong.

As Designer at Unboxed, Lawrence, reflects: “it’s the ultimate paradox.” If I spend my whole life believing that people cannot be trusted, then I’ll never form connections with people that are authentic and long-lasting enough for me to be shown otherwise. Because trust, ultimately, is fundamental to connection and so in order to create the emotionally corrective experience that allows me to reap the benefits of connection - I first need to address the narrative in my mind blocking me from trusting. The feeling of fear, discomfort and uncertainty that follows? That feeling, in its essence, is vulnerability.

While, ‘distrust’ may be my vulnerability to overcome. Perhaps, for a fellow team member, it may be, ‘a fear of failure,’ for another team member, it may be ‘the shame they feel over a mental health struggle,’ and for another, ‘financial stressors.’ Now, refer back to that scene I depicted in the subheading prior to this one: 2 or 3 or 4 or 20 people in the same room - each individual with their own unique story, personality and mixed bag of affordances and disaffordances. “It’s hard enough to figure this out on an individual level. Doing this on a team level within a work environment where you’ve not necessarily chosen your co-workers in the same way that you would choose who you’re vulnerable with in your personal life - you just hope that they’ll be people that are worth connecting with but it can be difficult.”

Lawrence continued: “I think many people shut down in order to reduce the complexity. As a coping mechanism, they may compartmentalise and say, I'm just going to do my work.” The problem with this is that while the concept of “bringing your whole self to work” may be stricken with controversy… That teams made up of diverse groups of people operating within a culture in which there is psychological safety, consistent communication, connection and a sense of belonging outperform teams who do not - is a fact that remains unrefuted. And, that a willingness to be vulnerable is fundamental to creating this type of environment is also a fact backed by decades of research from scores of social scientists.

“Okay, all this is interesting but how does ‘Agile’ fit in?”

I first became interested in the connection between the concept of “vulnerability” linking with Agile practices after watching this video from Interaction Design Foundation’s Lauren Klein who said: “to me, iterating is kind of a big part of what makes agile, agile. It’s what makes agile work. And, it’s the only thing that makes me as a designer okay with sometimes letting things out into the world that I know aren’t quite right. You know - we’re going to have a chance to get feedback on them and then make them better. That’s the deal we’ve made.” Hearing this was a bit of an “aha” moment for me and triggered a scurry of thoughts around vulnerability in relation to safety and resilience.

The philosophy of ‘Agile’ is rooted in an understanding of the nature of vulnerability within the context of complexity, volatility and uncertainty. For Director at Unboxed, Martyn Evans, vulnerability lies in “giving people certainty when (he) knows that there isn’t any” which makes him feel that he could be “exposed as a fraud, unprofessional and not trustworthy.” So, with experience, he’s learnt that he can “relieve himself of that vulnerability by accepting early on that (he) doesn’t know all the answers.”

He went on to explain, “I think agile principles validate that position. They make it an applicable approach and give us a common language to speak about it. Now we can say, ‘we don’t know the answer and we can spend 3 months thinking about it and we still wouldn’t know as much as we’d know in 6 months. So, why don’t we start acting now and making decisions based on the information we have, get feedback and then find out how/where to go?’”

Herein lies the basic premise of 'Agile': it’s about people over process, willful collaboration over obligation and creating the best possible product or service rather than half-heartedly doing things just to be seen to be doing things. Most of all, it’s about having an ability to respond to and adapt to change. The Agile Manifesto’ which summarises this ideal albeit in slightly different words - was created in 2001 by a group of software developers and tech industry leads, who came to be known as the ‘Snowbird 17.'

They had gathered for a retreat against the backdrop of the Wasatch Mountains in Utah, USA to vent their frustrations over the hypocritical and prohibitive corporate culture, ubiquitous at the time, that they felt to be a barrier to the industry’s progression. And, though they all agreed that they were feeling frustrated, no one could agree on how to resolve this frustration. Here, again, you find the exact scenario depicted throughout this article: 17 people in a room together assimilating the problem at hand completely differently and trying to find a way to agree on the best path forward.

Ultimately, what they were able to agree on was that attempting to solve such a huge, complex problem all in one go would prove futile. And so based on this idea of breaking the problem up into small chunks and then collectively using whatever new information they encountered at each stage of the journey in order to respond and adapt - they thought about what kinds of team dynamic and work environment they would need to foster in order to enable the quality of cohesion and collaboration that could enable collective adaptation at pace. Consequently, 'Agile' as a philosophy was born and the values inherent were what they translated into ceremonies and habitual exercises that they embedded into their ways of working.

Practices and ceremonies such as sprints, stand up’s, show & tell’s etc. Over time, some of these practices have remained and some have become redundant but what has remained consistent and unchanging is the contract and shared language underpinning the “Agile'' philosophy and value set which say: “it’s okay not to know,” “it’s okay to make mistakes,” “it’s okay to be afraid,” “your vulnerabilities, fears and insecurities are safe here” “bit by bit, we’ll figure it out together.”

To Be… Or not to Be… [Vulnerable].

Is this the answer?

It was quite late in the evening by the time I found myself emerging out of the YouTube rabbithole of conversation and debate around vulnerability at work that lead to the writing of this article. Sifting through the adverts inviting me to pay for courses and this and that product that was going to be THE ONE solution to all of my problems, I found myself circling back to Mike Robbin’s TedTalk Presentation on “bringing your whole self to work.” In it, he shares his journey towards embracing authenticity and as with most journeys - it was hard and it was humbling but ultimately, he attributes this willingness to being authentic (and with that, being vulnerable) as the cornerstone to his success.

More importantly, he says that his success would have been meaningless without it. In spite of myself, I found myself sold on the idea. And, if I’d had any lingering doubts or fears then I found them soothed by Brene Brown’s final sentiment in the segment promoting her book, “Daring Greatly.” In it, she says: “If we are going to find our way out of disorder and back to each other, vulnerability is the path and courage is the light. To set down those lists of ‘what we’re supposed to be’ is brave. And, to support each other in the process of becoming real is perhaps the greatest single act of daring greatly.”

So… What do you think? Shall we try?

[TL;DR] How ‘Agile’ both enables and protects against ‘Vulnerability’

- Big, insurmountable projects are broken up into bite-sized and manageable pieces which reduces anxiety and builds confidence as each iteration is completed.

- Consensus: the process is structured in such a way that everybody participating understands that the work being shown is not complete.

- The iterative nature of Agile means that the designer / developer is secure in the fact that they will have an opportunity to improve on their work after receiving feedback.

- Operating in sprints allows for regular practice demonstrating work which builds confidence.

- Agile events embedded into sprints, e.g. ‘stand up’s, show & tells etc. ensure scheduled check-in’s to allow regular opportunities to ask for help / offer help / demonstrate work completed which strengthens relationships between team members.

- Consistent communication and regular collaboration reduces risk of tension and confrontation reducing anxiety and facilitating ease.

- Thus, enabling the psychological safety that team members need in order to practice safe vulnerability (openness and transparency) while protecting against future vulnerabilities within product design and service delivery (via consistent communication and effective collaboration).

- “Where fear of being vulnerable often relates to ‘uncertainty, risk and emotional exposure,’ agile processes are specifically designed to protect against ‘uncertainty, risk and exposure’ by fostering authentic connection amongst team members.”

- “When vulnerabilities are supported and processed through effective communication within psychologically safe environments’ these vulnerabilities can lead to resilience and increased capacity to support others, thus, compounding the strength of the team and as consequence, the quality of products and services delivered.”

Up Next… IN CONVERSATION - Director at Unboxed, Martyn Evans, and I talk about vulnerability and leadership.