“The types of problems we're addressing in the public sector are really wicked problems. They’re entangled within other systems that often fall outside of the project scope, which can challenge the ability to create the kind of impact that is hoped for.”

Emma McGowan, Head of Corporate Transformation at Hackney Council

Service design projects, particularly within local government, are not isolated pieces of work. Factors outside of our control, like time and funding, can influence the success of a project. However, there are also many factors within our control - but how do they influence the success or failure of a project?

This article was prompted by reflections on two local council projects we have been working on at Unboxed which include:

- a long-running project to replace legacy back-office planning systems. The project has made slow and steady progress, with a clear focus on effective collaboration across multiple councils but is taking time to become a full end-to-end service.

- a short-term project to create a new brokerage management system within adult social care. A lot of progress was made very quickly but under extreme time pressure, the service area resorted to buying an off-the-shelf solution.

At first glance, both projects seemed not to have met our expectations of ‘success’. The first, has a slow adoption rate by service users. The second reverted to an off-the-shelf solution.

We took these reflections to 4 digital leads and service designers working within the UK public sector:

- Will Callaghan, Product and Project Lead at LocalGov Drupal

- Emma McGowan, Head of Transformation at Hackney Council

- Angela Orviz, Service Designer

- Matt Wood-Hill, Head of Digital Planning Software at the Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC)

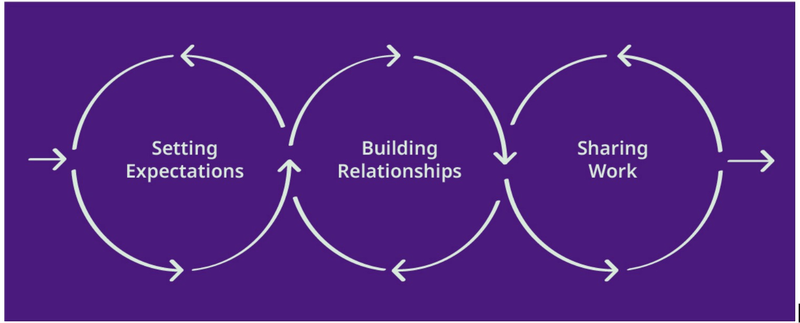

Our insights from these conversations identified three recurring themes for successful service design in local government:

- setting expectations

- building relationships

- sharing work

Setting expectations to get ‘buy-in’

“Having a clear and consistent vision, clearly communicated, really helps. This involves setting expectations in terms of behaviours and letting everyone know what the short, medium and long term look like and where the uncertainty is going to be.”

Matt Wood-Hill

Having a shared, consistent vision brings benefits within and beyond the scope of the project. It allows agencies and internal teams to work together towards a common goal. It can also generate ‘buy-in’ for your approach from the wider organisation and with other councils. But as Matt pointed out, it takes work.

“This is where I’ve seen projects be really successful - good, clear and consistent communication with a lot of legwork done upfront to create the right environment for people to work together, new team members to onboard and projects to scale.”

Matt Wood-Hill

As anyone working within the public sector will know, gaining ‘buy-in’ for both the intended outcomes and the approach is important if you want to scale the outcomes. Decision-makers need to take ownership of the product. This means internal stakeholders investing time in the project - not just attending meetings but having an holistic view of the project and an in-depth understanding of why decisions are being made. This understanding comes from being involved at every stage.

Finding project advocates

How do you communicate this clear vision? Your product owner needs to be an advocate for the project among other stakeholders. This isn’t easy in local government. Internal teams are often overstretched, no matter how committed they are to the vision.

It’s important to set this expectation of the product owner at the outset and reinforce advocacy as a non-negotiable requirement for success. It’s a challenge we put to our clients. Councils are making a huge commitment of money to deliver something new - this investment should be supported and validated by internal advocacy.

What happens when you don’t get this commitment?

You can end up with challenges when it comes to rolling out the product or changes to a service. We’ve seen this in our recent work in Adult Social Care. We worked with the service area to uncover user needs, test and iterate prototypes and build a back-end product. But because of the fast nature of the project, we didn't spend as much time ensuring that key stakeholders owned the product and process. This led to hesitation and push back when rolling out the new tool.

At Unboxed, we talk about working ‘with, not for’. Working ‘with’ can be at many different levels, not just those people who are directly involved. By setting clear expectations and fostering strong relationships early on and across the board, we might have found it easier to collectively compromise when we needed to.

It’s important to build these kinds of relationships within service design to allow you to deal with challenges together.

Building relationships that allow for challenge

“You can only challenge people when they trust you.”

Emma McGowan

Trust. That’s perhaps the most important and the most difficult thing about building the right environment for successful service design in the public sector. Service design doesn’t work without challenge, and challenge doesn’t work without trust.

How do we build trust? Another ‘T’. Time. We need to spend time with the people who are delivering the service.

“Showing that you are understanding and listening is important because if they don’t see that you’re actually listening and understanding their needs then it doesn’t work.”

Angela Orviz

We’ve found that trust comes through demonstration. Being there, listening, understanding. Only then can we challenge a process. Because service design does need to be a little bit disruptive, pushing boundaries and questioning why things are done in a certain way. People are more responsive to this type of challenge when they trust the people who are making it.

Avoiding disengagement

The fact is relationships can be hard work. We often talk about building relationships as something that happens at the beginning of a project, but like any relationship these connections need to be nurtured.

As service designers, we need to constantly check back in and make sure people still feel involved. There’s a risk that we engage people a lot at the beginning and then get stuck into the process, allowing people to become disengaged.

“I was told that some people in the project felt that we were moving forward without them. We decided to run a workshop so that they could see where we were, where we’re going and how we’ll consult with them.

Sometimes you need a lot of ears from people that you trust to tell you that things are not well.”

Angela Orviz

It’s important for everyone to acknowledge that service design isn’t a quick win. It’s slow, it takes time and relationships need to be nourished around the process. This is what allows us to take a step back and get out of the ‘ship-ship-ship’ mentality (as Emma referred to it).

Strong, trusting relationships give people the space and confidence to zoom out and be honest about whether the approach is right. If you trust each other, this reflection and re-evaluation won’t impact the project because they trust you and the process. Once again, the legwork pays off.

Stepping out: the challenge of the service design legacy

Emma reminded us that the value of being an external agency is that our perspective gives us freedom to challenge a bit more than an internal person might.

Yet we also face the challenge of ‘stepping out’. We put so much emphasis on building relationships but at some point we’re going to leave. This can have a huge impact on the longevity of the product and process that we’ve advocated for. We need internal champions who understand and trust the approach, the product and the process. So the emphasis is not just on building relationships between Unboxed and the client, but on building relationships within the council, so that they have a strong base to work from once we’re gone.

Sharing work

This kind of legacy relies on taking people on a journey with you. The trust we’ve talked about is maintained by a constant process of sharing work. Sharing work is a great tactic for keeping people engaged, opening yourself up to feedback and encouraging others to do the same. Again, it’s about building trust, being honest about our blockers, our challenges and what we’re working on right now.

If we zoom out a bit more, we can consider how other councils can benefit from what we’re learning and sharing.

“When I’m working on something, my first thought is what’s the wider value for everybody else? Who else can benefit from what we’ve been doing?”

Will Callaghan

Will talked about different approaches such as creating working groups.

“Get people into the same room and see what resonates with them. Encourage people to ask - can we work on this together?”

He also spoke about the importance of writing blogs: “I read somewhere that blogs are like having a human API. They are a simple way to document and share what you’re doing, while you’re doing it, and it gives other people an easy way of getting in touch."

Sharing work isn’t just about collaboration within the project. It’s about the ‘ripple effect’ beyond the thing that you’re doing. As Emma pointed out, many councils are looking for the same outcomes - “We need to stop thinking about problems affecting only one council. Every council is likely to have a similar problem. How can we work on these together?”

How can we support this kind of sharing as service designers? It goes back to our ‘legacy’ - we should be helping to establish a culture of sharing and reflection, giving people the tools and capability to collaborate in different ways. That might be through working groups, blogs, workshops, design crits or even teaching people how to use Miro. We need to do these things ourselves throughout the project while encouraging others to give them a go. If we don’t bring people on the journey, we can’t expect them to talk about how they got there once we leave.

The need to deliver tangible value

People might see that we’re collaborative, user-centred, thinking differently - but if we’re never successfully delivering anything then people start to lose faith in service design as a process. They’re thinking, “I’ve given you hours of my time talking about process, co-designing and so on, but what’s the result?”

As service designers, if we’re constantly thinking about shifting mindsets and doing something differently, but not delivering anything, that will influence people’s perception of value and as a result their willingness to engage.

It’s much harder to get people’s time if they can’t see where the impact of that will be. As service designers, we need to give equal value to the end-product as much as the process because they are inherently linked to each other and to the ultimate impact and outcome of the project.

Consider your lasting impression

No matter how good and interesting your process has been, it’s the last taste in their mouth that will have the enduring impression on the client.

A few weeks ago, in Hackney, we were in a really happy phase of the project. Everything was moving really smoothly, we had built really strong relationships. They had faith in what we were going to deliver. But then we hit a technical challenge with data migration. The process started to drag a little. We had to refocus on iterating a particular output. We could see people losing faith in our ability. We saw we had to show that we could deliver the new system because if we didn’t it would undermine our whole approach.

Were they thinking: “We heard you and understood you. We saw that you were listening to us throughout the process. You built this prototype and delivered this whole system. We thought it was all working but it’s not doing it quite how we were expecting now because there have been some hiccups…so was this the wrong approach?”

This made us consider how the output isn’t detached from the process. This is what we’re leaving them with. It’s more to do with developing products than redesigning a process or an internal service. But so often these days service design is so closely linked to delivering products. Especially at Unboxed.

Yet Emma and others talked about how their opinion of service design is more reflective of process and less on the output. The cultural and mindset shift as well as the more intangible values leading to success or failure.

Image: Creating an environment for successful service design

Finding the sweet spot

So it’s almost like the sweet spot or the balance or the success is found in between those two places - delivering output and the softer legacy. If you swing too far to the side of output only, you don’t have the people, culture, trust and all the components necessary for good delivery. But if you swing too far to the other side and focus only on mindset-shift then people will lose faith anyway. Delivery and output is having something tangible that works well and validates the faith that people have put in us as service designers.

From our perspective, success relies both on the strength of the relationships that you build as well as the quality of processes and set up. It’s not just about outputs.

Adapting to the needs of a project

“I don't think there's a one size fits all.”

Matt Wood-Hill

Each project and appetite for service design in local government will require a slightly different approach. We’ve found when working on projects that putting time and energy into setting expectations, building relationships and sharing work will ensure success and leave a lasting legacy for change.

Find out more

This article was prompted by reflections on Unboxed's recent work with two local authorities. Read more about these projects and the background to this article.

We discussed the themes of this article with other members of Unboxed’s design team in our Thoughts Unboxed podcast. If you feel you have something to contribute, let us know using the social links below.

Ali will also be leading a workshop in collaboration with our friends from Live|Work at Service Design in Government to identify other barriers and how we might navigate them. We’d love to see you there.

Follow our progress on: LinkedIn, Twitter, or Instagram

With thanks to Kassie Paschke for her support and contribution to research and writing for this piece.